Understanding the Nature of Wide and Close Play in the Martial Tradition of Fiore dei Liberi

Greg Mele

This article was originally written in 2008. It has been transcribed by members of the Malta Historical Fencing Association and reproduced here with the kind permission of Mr. Mele of the Chicago Swordplay Guild.

The Italian masters-at-arms of the Middle Ages and early Renaissance recognized that the judgment and management of distance was paramount to a martial artist. The control of distance was critical to how Fiore dei Liberi conceptualized his techniques, or “plays”, which he divided into two categories, one meant to maximize range, and one meant to collapse it. These two distinctions are:

Zogho Stretto (close or narrow[1] play) is the measure at which dei Liberi describes all abrazare (grappling) and dagger combat occurring. When fighting with longer weapons, it is the range at which one uses those same techniques: hilt/shaft strikes, grabs of the opponent’s sword arm, body, or head and includes body to-body contact such as throws.

Zogho Largo (wide play) only appears when discussing long weapons, such as the sword, spear or axe. At this measure, combatants may use the weapon’s edge and point, bind or grab the weapon’s head and, depending on the weapon’s length, make long-range unarmed attacks, such as kicks. Grabs will not reach any deeper than the opponent’s elbow; body-to-body contact is not possible.

Zogho Largo and Zogho Stretto are distinctions of how measure affects technique, not a definition of how or when you first come into distance. For example, all dagger combat is part of Zogho Stretto, since even the longest range knife attack occurs in grappling range, regardless of whether the opponent steps in to strike. Dei Liberi also introduced a third, more conceptual division, which was the bridge between these two types of play. Later elaborated upon by Filippo Vadi and the Bolognese masters, this was called the mezza spada (half-sword). This is the distance at which both combatants’ weapons will cross in the middle when the opponents strike at one another with the same blow. But the principle importance of the half-sword is tactical. Vadi first introduces this idea in chapter three of his treatise, where, after discussing how to “hammer him with blows”, the master demonstrates that the half-sword is the range in which we move from wide to close play:

When he comes to the half sword / close towards him, as reason requires/ leave the wide distance and assail him.

Because the half-sword (or half-axe, half-spear, etc.) is the bridge between Zogho Largo and Zogho Stretto, it is the one place where the combatant may use both sets of techniques. Any further away and he can only play “wide” unless he first closes distance; any closer to the opponent and he can only play “narrow” unless he first increases measure.

COMING TO THE CROSS

The best way to understand when you are in Largo and when you are in Stretto is to understand what happens in the bind. Fiore dei Liberi defines three types of parry, based on a crossing at one of the three parts of the blade the tutta (forte), mezza (middle third) and the punta (debole):

These two masters are here crossed at full-sword. And what one can do, the other can do, that is that one can do all plays of sword with the crossing. But the crossing is of three types which are full-sword (tutta spada) and point-of-sword (punta della spada). And the one who is crossed at full-sword can stay a little. And the one who is crossed at mid-sword (mezza spada) can stay less. And the one who is at point-of-sword cannot stay at all. So that one has indeed the sword in three positions, that is, in little less than nothing

The play of Zogho Largo is taught by three magistri (masters), the first two of whom are related to the three incrossada: the first describes how to play from the crossing at the punta, while the second shows the crossing at the mezza spada. The third master is a contrario (counter), showing how to transition into close quarters. Zogho Stretto is taught by only one master, who crosses at the half sword in the Getty Ms and at the tutta in the Pissani-Dossi.

The incrossada at Zogho Largo are shown with the left foot forward. Although Fiore is silent on the matter, Vadi specifically addresses this foot placement, when discussing how to parry a strike:

When you parry the backhand, keep forward / the right foot and parry as said / when parrying the forehand / then you will have the left foot forward.[2]

Conversely, the incrossada at Zogho Stretto are shown with the right foot forward. Again, dei Liberi does not overtly discuss this, but the reversed stance changes the relative measure between the combatants’ dominant sides, and affects which line is open.

Zogho Largo

The twenty techniques of Zogho Largo principally occur on the inside line: the Scholar only steps to the outside in five instances. The first is a small step of the left foot in a play called the Colpo di Villano (villain’s blow), the second and third are grappling techniques that occur after a failed counter to a thrust, the fourth is a follow-on to a feint, and the fifth is its counter. By understanding when and why four of these five plays move to the outside, we can get a clear understanding of the relationship between wide and close play in the dei Liberi School.

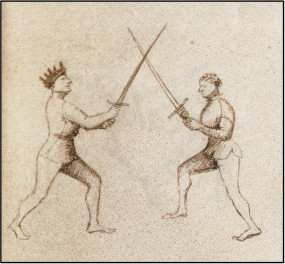

Figure 1: The First Crossing of the Sword in Wide Play: The Cross at the Point

The bind is very weak in the crossing of the punta (‘the one who is at the point cannot stay at all”) and as such there are only two possibilities, based on who is more forceful in the bind. If the Scholar (defender) wins the bind, he presses through the opponent’s strike, striking him in the head or “stands the point to his face”. However, if he loses the bind he simply lets the opponent’s blow push through his guard and strikes him with a backhand to the side of the head.

Most of the techniques of wide play are taught by the second master, who crosses at the mezza spada. His initial plays are based on the same lessons of blade pressure in the bind taught by the first master, only from a different, stronger crossing on the blade. The other techniques used in the Largo section focus on cuts and thrusts with the last third of the blade. They do not contain any hilt strikes, throws or body to body contact, as the Zogho Stretto techniques do. They do contain two kicks and an elbow-push. This reflects an issue of measure, rather than line, because the two stomp kicks are long-range unarmed techniques – almost equivalent in reach to a sword cut from the bind.

The most likely reason for the left foot crossing throughout wide play is not best described by Fiore or Vadi, but by the Bolognese master, Antonio Manciolino, who carefully describes the relationship between Largo, Stretto and playing from the mezza spada:

As you play with the two-handed sword in the gioco largo, you should keep your eye on the part of the opponent’s sword from half-blade to the tip. However, once you are at the half-sword, you should look at your opponent’s left hand, since it is with it that he may come to grapples. The art of the half sword is necessary to the curriculum of anyone who wishes to become a good Player. If you were only skilled in the gioco Largo, and found yourself in the Stretto, you would be compelled with shame and danger to pull back, thus often relinquishing victory to your opponent – or at least betraying your lack of half-swording skills to those who watch.[3]

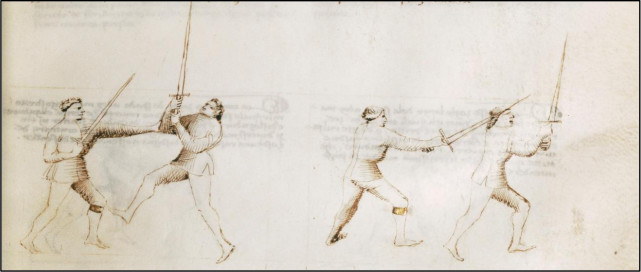

Figure 2: The Second Crossing of the Sword in Wide Play: The cross at the Half-Sword

By crossing with the opposite foot forward, the Scholar completely closes the opponent out of his inside line, can freely play with his sword’s point and edges, and puts his dominant hand further from his opponent’s left hand, forcing him to pass in if he wishes to grapple. Conversely, having the left leg forward allows the Scholar to quickly make his own grabs to the opponent’s sword, or sword arm without having to step at all.

Finally, the Scholar can still pass in with his right foot as he makes a follow-on attack and remain in wide play.

Zogho Stretto

The second division of combat is Zogho Stretto, which is best defined by Fiore dei Liberi himself:

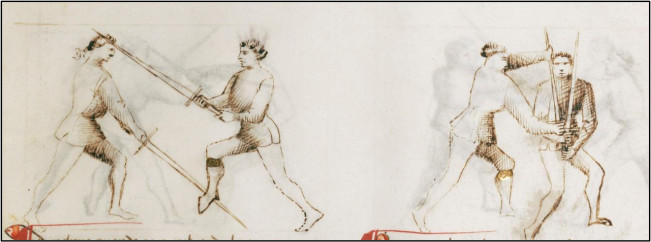

Figure 3: The Crossing of the Sword in Narrow Play

Having found you entirely uncovered, I will strike you in the head for certain. And if I wish to pass forward with my rear foot, I will be able to do many zoghi stretti against you, that is, binds, disarms and grappling.

The master demonstrates twenty-five plays of Zogho Stretto, all of which come from a crossing with the right foot forward. While this crossing seems more “natural”, as it often arises from two simultaneous blows, it does not close the Scholar’s inside line as strongly, making him susceptible to follow-on attacks in the same line. It also brings his sword arm closer to his opponent’s grappling hand.

Finally, if he wishes to pass in with the rear foot he must pass to the opponent’s outside, thereby winding to his (the opponent’s) strong side, and collapsing measure. While the Scholar can now grapple, he is also vulnerable to being counter-grappled.

COMPARING TECHNIQUES OF WIDE AND CLOSE PLAY

As was mentioned above, it is a gross simplification to say that Zogho Largo involves cuts and thrusts, whereas Zogho Stretto involves grips or disarms, as these are found in both types of play. The difference is where and how these plays occur. This is best explained by comparing a few specific examples of techniques that appear in both types of play.

GRABBING THE OPPONENT’S SWORD

Figure 4: Grabbing the sword in Zogho Largo. From the cross at mezza spada, the Scholar grips the sword’s punta and cuts the Player in the head. Should the Player try to cover by turning to left posta di finestra, the Scholar may also execute a shin stomp as a distraction.

Figure 5: Grabbing the sword in Zogho Stretto. From the cross at mezza spada, the Scholar passes in, gripping the Player’s wrist, trapping his weapon and threatening with a thrust.

One of the first plays of the second Master of Zogho Largo involves grabbing the opponent’s sword when the weapons bind. As the blades cross, the pressure is more or less even in the bind, and the opponent’s point threatens the Scholar; he cannot safely leave the bind without being hit. Therefore, the Scholar releases his sword’s hilt with his left hand and grasps the Player’s blade by the punta. He then immediately uncrosses and makes a one-handed cut to the Player’s face. (See Figure 4.) By keeping the right leg refused, the Scholar’s sword hand remains completely out of reach of the Player, and he can freely uncross and cut the Player in the head or the left hand, should he attempt a grapple. Conversely, in the corresponding play of Zogho Stretto the Scholar comes to the half-sword with his right foot forward.

He then passes in with his left foot, as he reaches between the opponent’s hands with his left hand, in the position of 12 o’clock (little finger up). He grasps the wrist of the Player’s sword arm and makes a short, counter-clockwise rotation of his hand, as he draws his sword back into posta di finestra. (See Figure 5).

Note that when the combatants cross with both of their right feet forward at the mezza spada, i.e.: the Master of Zogho Stretto, that the forward pass of the left foot will bring the Scholar much closer to the Player. Consequently, he must retract his sword in order to threaten him with a thrust, as he is too close to execute an extended blow.

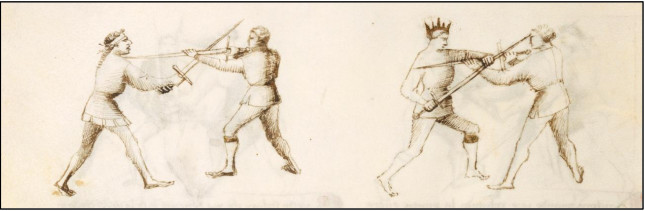

Figure 6: An elbow push from the crossing of Zogho Largo drives the Player away from the Scholar, requiring him to pass in and make a fully-extended cut.

ELBOW PUSH

Another recurring technique throughout dei Liberi’s treatise is the elbow push, which occurs both in the crossing of Zogho Largo and Stretto.[4] By comparing them, we can again see how the subtle difference of which leg is forward during the crossing at the half-sword affects the final measure of the play. In the Largo version of the elbow push, the Scholar and Player again come to the bind. The Scholar immediately releases his hilt with his left hand, and does an elbow push to the Player’s sword arm, spinning him away and to his own left. From here, he pursues with a pass forward of the rear (right) foot, and cuts him across the back of the head. (See Figure 6.)

Figure 7: An elbow push from the crossing of Zogho Stretto. Although the Player is still turned about, he is in virtual, body-to-body contact with the Scholar.

Conversely, in the Stretto version, the Scholar and Player come to the cross, with their right feet forward. As the Scholar parries, he passes forward with his rear (left foot) and makes the elbow push, spinning the Player away and to his own left. From here, the Scholar throws his sword about the Player’s neck and cuts his throat. (See Figure 7.) Despite both being the same basic technique, performed from the crossing at the mezza spada, the relative positions of the body in the cross changes the nature and measure of the play.

Whereas the first play required him to pursue his opponent to even reach him with a fully extended cut, the second play immediately puts the combatants in body-to-body contact.

TRANSITIONING FROM WIDE TO CLOSE PLAY

Although grapples in wide play focus on long-distance actions such as grabbing the sword or kicking the knee or groin with a straight leg, there are two grappling techniques that do appear in this section, where they occur as follow-on techniques. In both, the technique that precedes them has the Scholar pass forward with his right foot, putting him in the position of the master of Zogho Stretto!

The first of these techniques is called the scambiar di punta (the exchange of thrusts). The Scholar assumes tutta porta di ferro, posta di finestra or posta di donna. The opponent enters into measure with a thrust to the Scholar’s face. The Scholar strikes with the true-edge of his sword as he steps forward left with his left foot, stepping into the line of the attack, and parries the blow with his arms well-extended from his body and his hands low, at about the height of his groin. Passing forward with the right foot, he thrusts the Player in the throat. However, should the thrust miss the target, glance off of any armour, etc., the Scholar is now in a bind on the tutta of the sword, with his right foot forward. This is the position of the master of Zogho Stretto. Applying this master’s lesson, the Scholar immediately passes to the outside with his rear (left) foot and grips the Player’s hilt between his hands. Locking down the opponent’s sword, he thrusts under his arm to his face. (Fig. 8)

Figure 8: The Scambiar di Punta and the prese of Zogho Stretto made as an immediate follow-on technique, should the exchange of thrusts fail.

The second play that leads to a transition from wide to close play is another thrust counter, the rompere di punta (breaking the thrust). The Scholar begins in tutta porta di ferro, posta di finestra, or posta di donna. As the opponent passes in with a thrust to his chest or face, the Scholar makes a small traverse with his left foot to his forward left while striking up with his sword into the attack. Making a mezza volta (a passing step that rotates the Scholar’s body to face the other side of the centerline) with his right foot, he presses down with his sword, driving the opponent’s weapon into the ground. He then immediately cuts up with his false edge to the opponent’s throat. He finishes with a descending backhand to the opponent’s head as he passes back with his right foot, and then withdraws from measure.

Figure 9: The Rompere di Punta and a follow on technique of Zogho Stretto, should the opponent defend against the rompere di punta.

However, if the opponent is prepared when his sword is driven into the ground, he can parry the false edge cut by pulling his hands up into a left posta di finestra. As before, the Scholar now finds himself in an incrossada with his right foot forward.

As the opponent parries the false edge blow, the Scholar releases his left hand from his hilt and hooks it over his opponent’s wrist. Passing to the outside with his left foot, he grabs his blade in his left hand and presses it forward into the enemy’s neck, as he wrenches back with the hilt. The pressure of this bind is then used to bear him to the ground. (Fig 9)

Throughout the Getty Manuscript, dei Liberi uses a bridging technique that leads from the end of one section into the next. For example, abrazare ends with the use of a small stick in a way that relates to dagger combat, while the dagger section ends with plays of the dagger vs. the sword, leading into the instruction on swordsmanship.

In the same way, the final play in the section of Zogho Largo is the punta corta (shortened point) and its counter. This time the Scholar is the attacker, and he closes measure with a pass of the right foot as he makes a horizontal blow to the left side of his opponent’s head. The opponent passes in with his right foot and attempts to parry. But as he does so the Scholar’s blow falls short, just touching his blade. The Scholar instantly cuts around to the other side and passes in with his left foot. He grasps his blade in his left hand and thrusts the opponent in the face.

Figure 10: The Transition from Wide to Narrow Play: The Punta Corta and its Contrario. As the attacker closes measure from the crossing of Zogho Stretto with the punta corta, the defender responds by using a play of Zogho Stretto himself..

To counter this technique, the opponent waits until the Scholar begins to pass to the outside. He simply turns his hand to his right side, letting the Scholar run onto his point. Passing in with his left foot, the opponent grabs his own sword by the blade and completes the thrust. Considering the use of bridging techniques and repetition used throughout the manuscript, it is likely no coincidence that the punta corta is the link between wide and close play, nor that the follow-on to the exchange of thrusts is also the first play that dei Liberi teaches in his section on Zogho Stretto!

CONCLUSION

The techniques of both Zogho Largo and Stretto begin at a distance where either person can strike the partner’s head or arms with the last third of his sword. This is essentially one-step range, and if one or both opponents simply stepped forward to strike at the other, the sword will most naturally cross in the middle. Although line appears to have a role in these techniques, with Largo techniques favoring the inside line, and Stretto techniques favoring the outside line, it is actually a secondary concern to the issue of measure. Dei Liberi and Vadi instruct that Zogho Largo occurs while coming into measure, progresses up to the half-sword, and focuses primarily on cuts and thrusts, whereas Zogho Stretto plays begin at the half-sword, and involve grips, disarms and grappling. The crossing of the half-sword assumes prominence, for it is both the divider and unifier of the two types of play. At the crossing of the punta, the swordsman can only play in Largo; at the tutta he can only play in Stretto. But at the mezza spada, the swordsman can use the plays of both. By using its particular leg position in coming to the cross, the dei Liberi School sought to maintain maximum distance in wide play, and allow the strongest, fastest closing of distance in the close.

BILIOGRAPHY

Primary Sources

Dei Liberi, Fiore: Fior di Battaglia; Italy, 1410; J. Paul Getty Museum (Ms. Ludwig XV 13) 83.MR.183

____________: Fior di Battaglia; Italy, c.1400; Pierpoint Morgan Library (MS M.383)

____________: Flos Duellatorum; Italy, 1410; reprinted by Novati, Francesco, Flos Duellatorum, Il Fior di Battaglia di Maestro Fiore dei Liberi da Premariacco; Bergamo: Instituto Italiano d'Arte Grafiche, 1902.

Manciolino, Antonio: Opera Nova; 1531.

Marozzo, Achille: Opera Nova; Venice, 1536.

Silver, George: Brief Instructions on My Paradoxes of Defense; London, 1602 unpublished until Cyril Mathey, The Works of George Silver; London, 1896

Vadi, Fillipo: De Arte Gladiatoria Dimicandi; c.1482 – 87; translated by Luca Porzio and Gregory Mele in Arte Gladiatoria: 15th Century Swordsmanship of the Italian Master Filippo Vadi; Chivalry Bookshelf, Union City, CA 2002.

Secondary Sources

Anglo, Sydney. The Martial Arts of Renaissance Europe. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2000.

Malipiero, Massimo. Il Fior di battaglia di Fiore dei Liberi da Cividale: Il Codice Ludwing XV 13 del J. Paul Getty Museum. Udine: Ribis, 2006.

Rubboli, Marco; Cesari, Luca. Flos Duellatorum. Manuale di Arte del Combattimento del XV secolo. Rome: Il Cerchio Iniziative Editoriali, 2002.

____________: L'Arte della Spada: Trattato di scherma dell'inizio del XVI secolo. Rome: Il Cerchio Iniziative Editoriali, 2005.

Zanutto, D. Luigi. Fiore di Premariacco ed I Ludi e Le Feste Marziali e Civili in Friuli. Udine: D. Del Bianco,1907.

Notes and references

- 1. The Italian word stretto is one of those words that infuriates English-speakers new to the language, because it can translate as several related, but distinct, words in the English language, meaning “close”, “narrow” or “constrained”. In the context of fencing, all convey a sense that the distance between the opponents is tight, so I have chosen “narrow” for stretto as being the best counterpart to largo, or “wide”.

- 2. Filippo Vadi de Pisa, De Arte Gladiatoria Dimicandi, Chapter 11. Translation mine.

- 3. Antonio Manciolino, Opera Nova (1531), Book I, Chapter I. Translation by Tom Leoni.

- 4. In this case, the stretto play is found in the section on the sword in one hand.